How Computers Store Data with Binary Numbers

Posted by Al Sweigart in misc

Programming and hacking in movies often involves streams of ones and zeros flowing across the screen. This looks mysterious and impressive, but what do these ones and zeros actually mean? You're probably aware that binary numbers (numbers written using only the two digits, zero and one) have something to do with computers but don't know why.

The answer is economics: binary is the simplest number system and it can be implemented with relatively inexpensive components for computer hardware. Binary, also called the base-2 number system, can represent all of the same numbers that our more familiar base-10 decimal number system can. Decimal has ten digits, 0 through 9. The following table shows the first 24 numbers in decimal and binary:

| Decimal | Binary | Decimal | Binary | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 12 | 1100 | |

| 1 | 1 | 13 | 1101 | |

| 2 | 10 | 14 | 1110 | |

| 3 | 11 | 15 | 1111 | |

| 4 | 100 | 16 | 10000 | |

| 5 | 101 | 17 | 10001 | |

| 6 | 110 | 18 | 10010 | |

| 7 | 111 | 19 | 10011 | |

| 8 | 1000 | 20 | 10100 | |

| 9 | 1001 | 21 | 10101 | |

| 10 | 1010 | 22 | 10110 | |

| 11 | 1011 | 23 | 10111 |

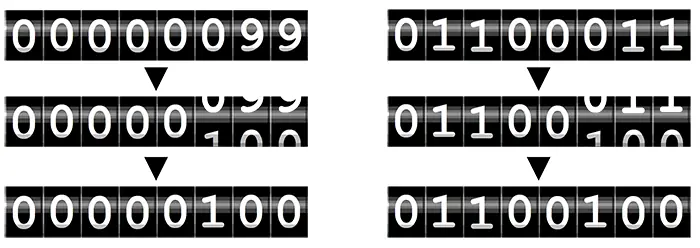

Think of the number systems as a mechanical odometer: when you reach the last digit, it resets back to zero while incrementing the next digit. In decimal the last digit is 9 and in binary the last digit is 1. The decimal number after 9 is 10 and the decimal number after 999 is 1000. Similarly, the binary number after 1 is 10 and the binary number after 111 is 1000. Although "10" in binary doesn't mean the same quantity as "ten" in decimal, but rather two. And "1000" in binary doesn't mean the same quantity as "one thousand" in decimal, but rather eight. You can view an interactive binary and decimal odometer at https://inventwithpython.com/odometer

Representing binary numbers with computer hardware is simpler than decimal because there are only two states to represent. For example, spinning-disc hard drives have microscopic spots that can be magnetized or not magnetized. Blu-Ray discs and DVDs have smooth "lands" and indented "pits" etched on the surface of the disk that will or won't reflect the disc player's laser, respectively. Circuits can have electric current flowing through them or no electric current. Even the spaces on paper punch cards for mid-20th century computers have a hole punched in them or no hole. These various hardware standards all have ways of representing two different states. On the other hand, it'd be expensive to create high-quality electronic components that are sensitive enough to detect the difference between ten different voltage levels with reliable accuracy. It's more economical to use simple components, and two binary states is as simple as you can get.

These binary digits are called bits for short. A single bit can represent two numbers, and eight bits (or one byte) can represent 2^8 or 256 numbers. This ranges from 0 to 255 in decimal and 0 to 11111111 in binary. This is similar to how a single decimal digit can represent ten numbers (0 to 9), an eight-digit decimal number can represent 10^8 or one hundred million numbers. Files on your computer are measured in how many bytes they take up:

- A kilobyte is 2^10 or 1,024 bytes.

- A megabyte is 2^20 or 1,048,576 bytes.

- A gigabyte is 2^30 or 1,073,741,824 bytes.

The text of Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet is about 135 kilobytes. A high-resolution photo is about 2 to 5 megabytes. A two-hour movie can be anywhere from 1 to 50 gigabytes depending on picture quality. Hard drive manufacturers and internet service providers will often use kilobyte, megabyte, and gigabyte to mean a flat one thousand, one million, or one billion because it allows them to overexaggerate how much capacity they provide. The reason corporations can blatantly lie about their numbers this way is because that's how the world works.

Once there is a way to represent binary numbers, you can represent numbers in any number system. You don't need to know the math behind converting from base-2 to base-10 and vice versa to write Python scripts that automate boring stuff. Python has functions to perform this math for you: calling bin(42) returns the string '0b101010'. The '0b' prefix is a convention for marking the number as in binary, instead of meaning "one hundred one thousand ten" in decimal. Meanwhile, calling int('101010', 2) converts binary-to-decimal and returns the integer 42. The 2 argument tells the int() function that '101010' is a base-2 binary number.

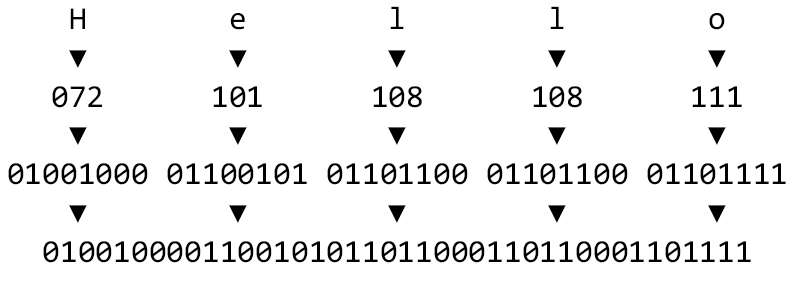

The ones and zeros of binary can not only represent any integer but also any form of data. Text can be stored on computers as binary numbers by assigning each letter, punctuation mark, or symbol a unique number. One early such scheme for this was ASCII, the American Symbolic Code for Information-Interchange. In ASCII, a capital letter "A" is represent by the number 65 (or 1000001 in binary), a "?" question mark is represented by the number 63, and the numeral 7 is represented by the number 55. The string 'Hello' is stored as the numbers 72, 101, 108, 108, and 111. When combined one after the other, this appears as a stream of binary: 10010001100101110110011011001101111.

Wow! Just like in those hacker movies!

However, these don't make sense without knowing how many digits are in each number. Representing 'Hello' in decimal as 72101108108111 is confusing because you wouldn't know if the first letter was represented by 7, 72, or 721. We can solve this by always using three digits for each letter and adding the leading zeros where needed: 72 becomes 072. The fifteen digits of 072101108108111 can be evenly split up into five groups of three digits each to represent the five letters. The same can be done in binary, where one byte (or eight bits) represents each letter. With the leading zeros, 'Hello' becomes 0100100001100101011011000110110001101111, as shown in this figure:

Large numbers can be tedious to write in binary, so programmers often view binary information in base-16 or hexadecimal. The numerals of hexadecimal (or simple, hex) range from 0 to 9, and then continue with the first six letters A to F like in the following table:

| Decimal | Hexadecimal | Binary | Decimal | Hexadecimal | Binary | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | C | 1100 | |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 13 | D | 1101 | |

| 2 | 2 | 10 | 14 | E | 1110 | |

| 3 | 3 | 11 | 15 | F | 1111 | |

| 4 | 4 | 100 | 16 | 10 | 10000 | |

| 5 | 5 | 101 | 17 | 11 | 10001 | |

| 6 | 6 | 110 | 18 | 12 | 10010 | |

| 7 | 7 | 111 | 19 | 13 | 10011 | |

| 8 | 8 | 1000 | 20 | 14 | 10100 | |

| 9 | 9 | 1001 | 21 | 15 | 10101 | |

| 10 | A | 1010 | 22 | 16 | 10110 | |

| 11 | B | 1011 | 23 | 17 | 10111 |

The single hex digit A represents the number ten, B represents eleven, and so on up to F, which represents 15. After this, we add another hexadecimal digit: the hexadecimal number 10 represents decimal 16. Python's hex() and int() functions convert between decimal and hexadecimal. Enter the following into the interactive shell:

>>> hex(42) # Convert decimal to hex

'0x2a'

>>> int('0x2a', 16) # Convert hex to decimal

42

>>> int('0x2A', 16) # Convert hex to decimal

42

>>> int('2A', 16) # Convert hex to decimal

42

The hex() function returns strings with a '0x' prefix to mark it as a hexadecimal number. The 16 argument tells the int() function that '2a' is written in base-16 hexadecimal.

The 'Hello' string can be shown in 40 binary digits, 0100100001100101011011000110110001101111, or more compactly with 10 hexadecimal digits, 48656c6c6f. This form is more convenient for programmers to read, and software called hex editors can display the binary data of a file this way.

ASCII was developed before the internet made international communication commonplace. It doesn't have numbers reserved for, say, Chinese characters. It's not just an encoding for English, but American English: the number 36 for the "$" dollar sign but no number for the British pound symbol. These issues were solved with Unicode Standard. Specifically, the UTF-8 encoding of the Unicode Standard uses one to four bytes to represent any possible character. UTF-8 is also backwards compatible with ASCII: 65 is a capital A in ASCII and UTF-8.

Python's ord() function takes a single-character string and returns the integer of its assigned Unicode code point. Python's chr() function does the opposite, taking an integer and return a single-character string of that number's assigned Unicode character. In this way, all text can be represented as numbers, and all numbers can be stored on computer hardware in binary form.

Engineers need to invent a way to encode each form of data as numbers. Photos and image are broken up into a two-dimensional grid of colored squares called pixels. Each pixel can use three bytes to represent how much red, green, and blue its color contains. Chapter 19 of Automate the Boring Stuff with Python covers image data in more detail. But for a short example, the numbers 255, 0, and 255 could represent a pixel with the maximum amount of red and blue but no green, resulting in a purple pixel.

Sound is made up of waves of compressed air that reach our ears, which our brains interpret as audio sensation. We can graph the intensity and frequency of these waves over time. The numbers of this graph can then be converted to binary numbers and stored on a computer, which can later control speakers to reproduce the sound. This is a simplification, but this is how binary numbers are stored in audio files such MP3s.

The data for several images combines with audio data to store videos. All forms of information can be encoded into numbers, converted into binary numbers, and then stored on computer hardware. There is, of course, a great deal more to it than this, but this is how ones and zeros represent the wide variety of data in our information age.