Use this link to get 70% off the Automate the Boring Stuff online video course.

Support me on Patreon

Now let’s see what Python can do with text. Almost all programs display text to the user, and the user enters text into programs through the keyboard. In this chapter, you’ll make your first program, which does both of these things. You’ll learn how to store text in variables, combine text, and display text on the screen. The program you’ll create displays the greeting Hello world! and asks for the user’s name.

In Python, text values are called strings. String values can be used just like integer or float values. You can store strings in variables. In code, string values start and end with a single quote, '. Enter this code into the interactive shell:

>>> spam = 'hello'

The single quotes tell Python where the string begins and ends. They are not part of the string value’s text. Now if you enter spam into the interactive shell, you’ll see the contents of the spam variable. Remember, Python evaluates variables as the value stored inside the variable. In this case, this is the string 'hello'.

>>> spam = 'hello'

>>> spam

'hello'

Strings can have any keyboard character in them and can be as long as you want. These are all examples of strings:

'hello'

'Hi there!'

'KITTENS'

'7 apples, 14 oranges, 3 lemons'

'Anything not pertaining to elephants is irrelephant.'

'A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away...'

'O*&#wY%*&OCfsdYO*&gfC%YO*&%3yc8r2'

You can combine string values with operators to make expressions, just as you did with integer and float values. When you combine two strings with the + operator, it’s called string concatenation. Enter 'Hello' + 'World!' into the interactive shell:

>>> 'Hello' + 'World!'

'HelloWorld!'

The expression evaluates to a single string value, 'HelloWorld!'. There is no space between the words because there was no space in either of the two concatenated strings, unlike in this example:

>>> 'Hello ' + 'World!'

'Hello World!'

The + operator works differently on string and integer values because they are different data types. All values have a data type. The data type of the value 'Hello' is a string. The data type of the value 5 is an integer. The data type tells Python what operators should do when evaluating expressions. The + operator concatenates string values, but adds integer and float values.

Until now, you’ve been typing instructions into IDLE’s interactive shell one at a time. When you write programs, though, you enter several instructions and have them run all at once, and this is what you’ll do next. It’s time to write your first program!

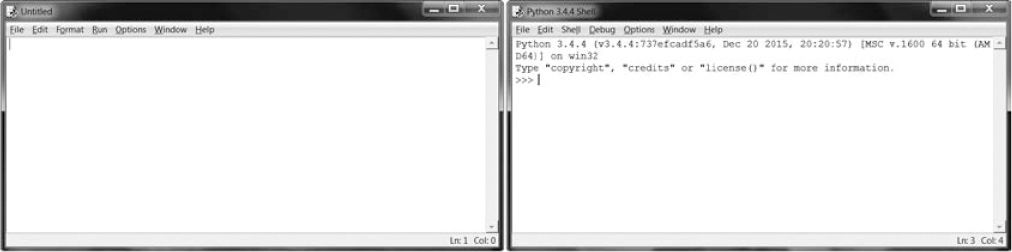

In addition to the interpreter, IDLE has another part called the file editor. To open it, click the File menu at the top of the interactive shell. Then select New File. A blank window will appear for you to type your program’s code into, as shown in Figure 2-1.

Figure 2-1: The file editor (left) and the interactive shell (right)

The two windows look similar, but just remember this: the interactive shell will have the >>> prompt, while the file editor will not.

It’s traditional for programmers to make their first program display Hello world! on the screen. You’ll create your own Hello World program now.

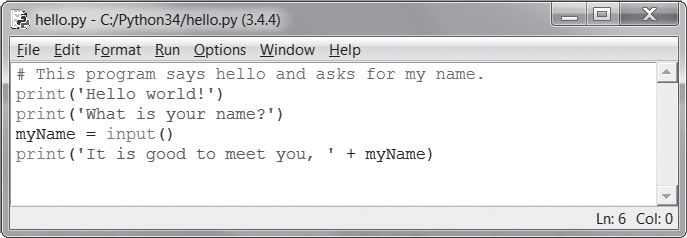

When you enter your program, remember not to enter the numbers at the beginning of each code line. They’re there so this book can refer to the code by line number. The bottom-right corner of the file editor will tell you where the blinking cursor is so you can check which line of code you are on. Figure 2-2 shows that the cursor is on line 1 (going up and down the editor) and column 0 (going left and right).

Figure 2-2: The bottom-right of the file editor tells you what line the cursor is on.

Enter the following text into the new file editor window. This is the program’s source code. It contains the instructions Python will follow when the program is run.

hello.py

1. # This program says hello and asks for my name.

2. print('Hello world!')

3. print('What is your name?')

4. myName = input()

5. print('It is good to meet you, ' + myName)

IDLE will write different types of instructions with different colors. After you’re done typing the code, the window should look like Figure 2-3.

Figure 2-3: The file editor will look like this after you enter your code.

Check to make sure your IDLE window looks the same.

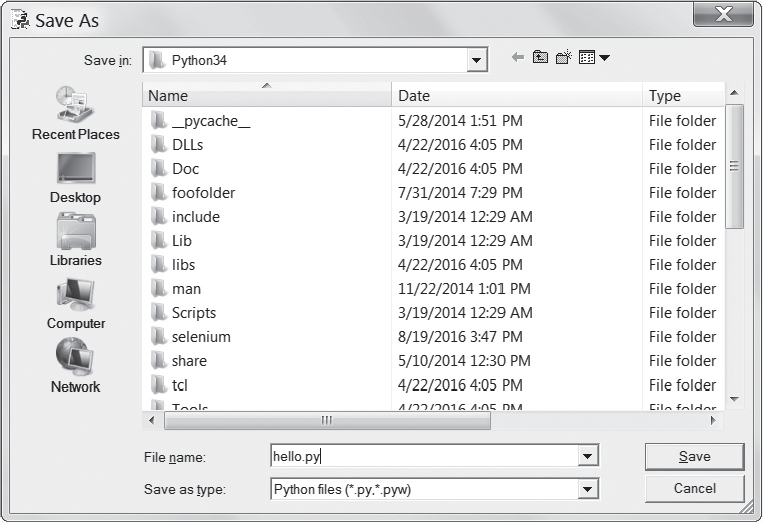

Once you’ve entered your source code, save it by clicking File  Save As. Or press CTRL-S to save with a keyboard shortcut. Figure 2-4 shows the Save As window that will open. Enter hello.py in the File name text field and then click Save.

Save As. Or press CTRL-S to save with a keyboard shortcut. Figure 2-4 shows the Save As window that will open. Enter hello.py in the File name text field and then click Save.

Figure 2-4: Saving the program

You should save your programs often while you write them. That way, if the computer crashes or you accidentally exit from IDLE, you won’t lose much work.

To load your previously saved program, click File  Open. Select the hello.py file in the window that appears and click the Open button. Your saved hello.py program will open in the file editor.

Open. Select the hello.py file in the window that appears and click the Open button. Your saved hello.py program will open in the file editor.

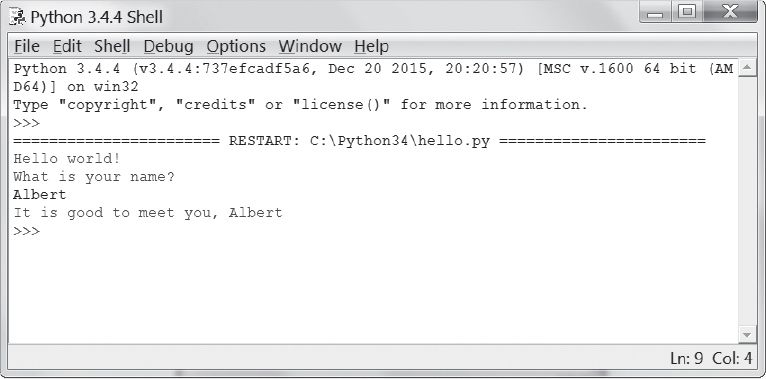

Now it’s time to run the program. Click Run  Run Module. Or just press F5 from the file editor (FN-5 on OS X). Your program will run in the interactive shell.

Run Module. Or just press F5 from the file editor (FN-5 on OS X). Your program will run in the interactive shell.

Enter your name when the program asks for it. This will look like Figure 2-5.

Figure 2-5: The interactive shell after you run hello.py

When you type your name and press ENTER, the program will greet you by name. Congratulations! You have written your first program and are now a computer programmer. Press F5 again to run the program a second time and enter another name.

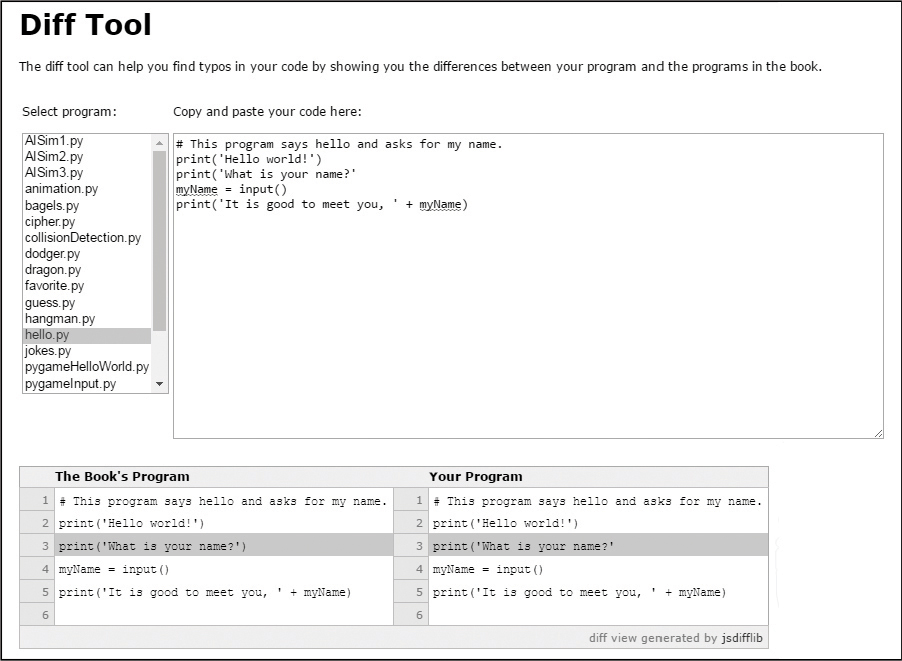

If you got an error, compare your code to this book’s code with the online diff tool at https://www.nostarch.com/inventwithpython#diff. Copy and paste your code from the file editor into the web page and click the Compare button. This tool will highlight any differences between your code and the code in this book, as shown in Figure 2-6.

While coding, if you get a NameError that looks like the following, that means you are using Python 2 instead of Python 3.

Hello world!

What is your name?

Albert

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "C:/Python26/test1.py", line 4, in <module>

myName = input()

File "<string>", line 1, in <module>

NameError: name 'Albert' is not defined

To fix the problem, install Python 3.4 and rerun the program. (See “Downloading and Installing Python” on page xxv.)

Figure 2-6: Using the diff tool at https://www.nostarch.com/inventwithpython#diff

Each line of code is an instruction interpreted by Python. These instructions make up the program. A computer program’s instructions are like the steps in a recipe. Python completes each instruction in order, beginning from the top of the program and moving downward.

The step where Python is currently working in the program is called the execution. When the program starts, the execution is at the first instruction. After executing the instruction, Python moves down to the next instruction.

Let’s look at each line of code to see what it’s doing. We’ll begin with line number 1.

The first line of the Hello World program is a comment:

1. # This program says hello and asks for my name.

Any text following a hash mark (#) is a comment. Comments are the programmer’s notes about what the code does; they are not written for Python but for you, the programmer. Python ignores comments when it runs a program. Programmers usually put a comment at the top of their code to give their program a title. The comment in the Hello World program tells you that the program says hello and asks for your name.

A function is kind of like a mini-program inside your program that contains several instructions for Python to execute. The great thing about functions is that you only need to know what they do, not how they do it. Python provides some built-in functions already. We use print() and input() in the Hello World program.

A function call is an instruction that tells Python to run the code inside a function. For example, your program calls the print() function to display a string on the screen. The print() function takes the string you type between the parentheses as input and displays that text on the screen.

Lines 2 and 3 of the Hello World program are calls to print():

2. print('Hello world!')

3. print('What is your name?')

A value between the parentheses in a function call is an argument. The argument on line 2’s print() function call is 'Hello world!', and the argument on line 3’s print() function call is 'What is your name?'. This is called passing the argument to the function.

Line 4 is an assignment statement with a variable, myName, and a function call, input():

4. myName = input()

When input() is called, the program waits for the user to enter text. The text string that the user enters becomes the value that the function call evaluates to. Function calls can be used in expressions anywhere a value can be used.

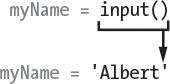

The value that the function call evaluates to is called the return value. (In fact, “the value a function call returns” means the same thing as “the value a function call evaluates to.”) In this case, the return value of the input() function is the string that the user entered: their name. If the user enters Albert, the input() function call evaluates to the string 'Albert'. The evaluation looks like this:

This is how the string value 'Albert' gets stored in the myName variable.

The last line in the Hello World program is another print() function call:

5. print('It is good to meet you, ' + myName)

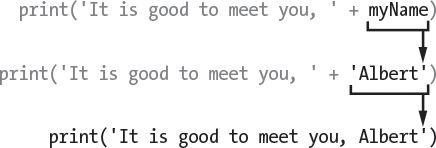

The expression 'It is good to meet you, ' + myName is between the parentheses of print(). Because arguments are always single values, Python will first evaluate this expression and then pass that value as the argument. If 'Albert' is stored in myName, the evaluation looks like this:

This is how the program greets the user by name.

Once the program executes the last line, it terminates or exits. This means the program stops running. Python forgets all of the values stored in variables, including the string stored in myName. If you run the program again and enter a different name, the program will think that is your name:

Hello world!

What is your name?

Carolyn

It is good to meet you, Carolyn

Remember, the computer does exactly what you program it to do. Computers are dumb and just follow the instructions you give them exactly. The computer doesn’t care if you type in your name, someone else’s name, or something silly. Type in anything you want. The computer will treat it the same way:

Hello world!

What is your name?

poop

It is good to meet you, poop

Giving variables descriptive names makes it easier to understand what a program does. You could have called the myName variable abrahamLincoln or nAmE, and Python would have run the program just the same. But those names don’t really tell you much about what information the variable might hold. As Chapter 1 discussed, if you were moving to a new house and you labeled every moving box Stuff, that wouldn’t be helpful at all! This book’s interactive shell examples use variable names like spam, eggs, and bacon because the variable names in these examples don’t matter. However, this book’s programs all use descriptive names, and so should your programs.

Variable names are case sensitive, which means the same variable name in a different case is considered a different variable. So spam, SPAM, Spam, and sPAM are four different variables in Python. They each contain their own separate values. It’s a bad idea to have differently cased variables in your program. Use descriptive names for your variables instead.

Variable names are usually lowercase. If there’s more than one word in the variable name, it’s a good idea to capitalize each word after the first. For example, the variable name whatIHadForBreakfastThisMorning is much easier to read than whatihadforbreakfastthismorning. Capitalizing your variables this way is called camel case (because it resembles the humps on a camel’s back), and it makes your code more readable. Programmers also prefer using shorter variable names to make code easier to understand: breakfast or foodThisMorning is more readable than whatIHadForBreakfastThisMorning. These are conventions—optional but standard ways of doing things in Python programming.

Once you understand how to use strings and functions, you can start making programs that interact with users. This is important because text is the main way the user and the computer will communicate with each other. The user enters text through the keyboard with the input() function, and the computer displays text on the screen with the print() function.

Strings are just values of a new data type. All values have a data type, and the data type of a value affects how the + operator functions.

Functions are used to carry out complicated instructions in your program. Python has many built-in functions that you’ll learn about in this book. Function calls can be used in expressions anywhere a value is used.

The instruction or step in your program where Python is currently working is called the execution. In Chapter 3, you’ll learn more about making the execution move in ways other than just straight down the program. Once you learn this, you’ll be ready to create games!